Washington, DC - On the Periodic Table of Elements, copper is designated as CU. The FTC’s lawsuit against Tommie Copper, Inc., the seller of copper-infused compression wear, suggests it may be time to conduct a periodic check of the elements in your ads to C that U have proof to back up your claims.

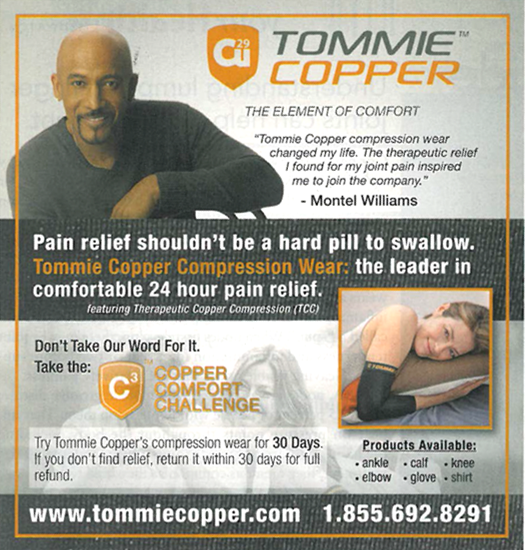

Haven’t seen a Tommie Copper ad? You really need to watch more TV. Through a massive marketing campaign, the company sold a line of stretchy sleeves for the elbow, knee, ankle, wrist, and calf, as well as shirts, tights, and socks. Selling for between about $30 and $70, the products weren’t just pitched as work-out wear for weekend warriors. The company marketed them as effective treatments for chronic or severe pain, including pain caused by multiple sclerosis (MS), arthritis, and fibromyalgia. What’s more, some ads claimed the compression garments would provide more effective pain relief than OTC drugs, prescription medication, or surgery.

What was the secret? According to promotional materials, it was the “patented 56 percent copper-infused nylon yarn with Tommie Copper’s exclusive multi-directional compression technology.” The defendants claimed the copper embedded in the products relieved pain due to “the well-known health benefits of copper,” including its purported “anti-inflammatory properties.”

Tommie Copper ads featured compelling stories recounting the pain that consumers suffered from “grade four bone-on-bone arthritis in both knees,” “RA [rheumatoid arthritis] with swelling and pain in my left knee,” “fibromyalgia for almost 30 years now,” psoriatic arthritis that causes “significant joint pain in the knee,” and “torn cartilage in my knee.” One consumer experienced complications from injuries when “an 18-wheeler ran the light and baseball batted my car. I was in a coma for a week.” He claimed all he had to do was “put the Tommie Copper shirt on” and “there was no more pain. It’s like the pain was gone.”

Not convinced yet? How about this endorsement from TV celebrity Montel Williams? “Since my diagnosis over 13 years ago with MS, I have been on a constant mission to manage my pain. I’ve tried more prescription medication than you can imagine. I dulled my pain, but it’s also dulled my life. Now, Tommie Copper is truly pain relief without a pill.”

And also – according to the FTC – without scientific evidence to back it up. The complaint charges that Tommie Copper and its chairman Thomas Kallish made false or unsubstantiated claims that the copper in the apparel relieves pain, that wearing the garments provides relief from chronic or severe pain and from pain and inflammation caused by serious diseases, and that the garments provide pain relief comparable to – or even better than – drugs or surgery.

The proposed order includes a $1.35 million financial remedy. In addition, the defendants have agreed to have appropriate evidence to support a broad range of future claims. If they sell devices or garments and make claims similar to the ones challenged in the complaint, they’ll need human clinical testing “sufficient in quality and quantity, based on standards generally accepted by relevant medical experts, when considered in light of the entire body of relevant and reliable scientific evidence, to substantiate that the representation is true.” The testing has to be randomized, double-blind, and placebo-controlled and conducted by qualified researchers.

If the defendants make health-related claims for any food, drug, cosmetic, device, or garment, they’ll need competent and reliable scientific evidence, defined as “tests, analyses, research, or studies that have been conducted and evaluated in an objective manner by qualified persons and that are generally accepted in the profession to yield accurate and reliable results.”

The settlement underscores the long-standing requirement that advertisers need appropriate science to support their representations. Furthermore, this isn’t the FTC’s first action against allegedly deceptive health claims for apparel. Regardless of the nature of the product or how it purports to provide a health benefit, established proof principles apply.